The famous story of the pregnant teen outed to her father by Target epitomizes the power of big data and advanced psychometrics to wring potent conclusions from seemingly innocuous snippets of data. Andreas Weigend, the former chief data scientist at Amazon has written a must-read book that dives deep into this topic. And an article in The Observer shows how these learnings are being applied to influence voters:

“With this, a computer can actually do psychology, it can predict and potentially control human behaviour. It’s what the scientologists try to do but much more powerful. It’s how you brainwash someone. It’s incredibly dangerous.

“It’s no exaggeration to say that minds can be changed. Behaviour can be predicted and controlled. I find it incredibly scary. I really do. Because nobody has really followed through on the possible consequences of all this. People don’t know it’s happening to them. Their attitudes are being changed behind their backs.”

– Jonathan Rust, Director, Cambridge University Psychometric Centre.

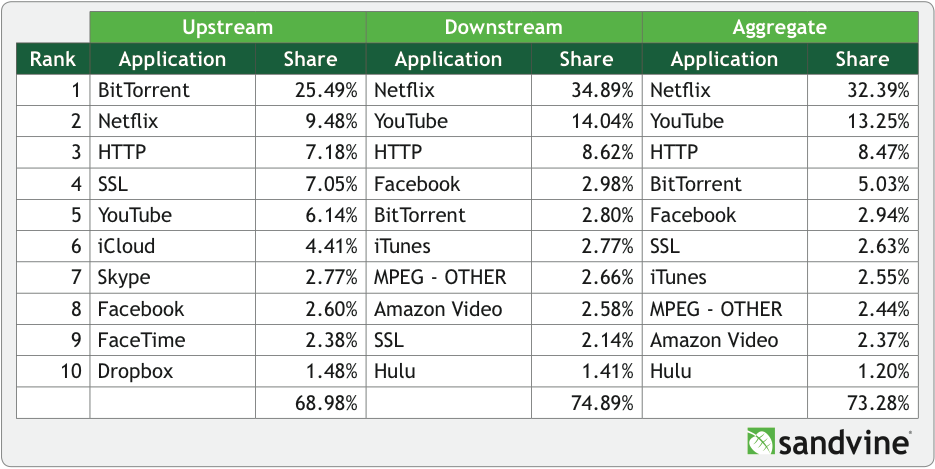

So metadata about your internet behavior is valuable, and can be used against your interests. This data is abundant, and Target only has a drop in the ocean compared to Facebook, Google and a few others. Thanks to its multi-pronged approach (Search, AdSense, Analytics, DNS, Chrome and Android), Google has detailed numbers on everything you do on the internet, and because it reads all your (sent and received) Gmail it knows most of your private thoughts. Facebook has a similar scope of insight into your mind and motivations.

Ajit Pai, the new FCC chairman, was a commissioner when the privacy regulations that were repealed last week were instituted last fall. He wrote a dissent arguing that applying internet privacy rules only to ISPs (Internet Service Providers, companies like AT&T or Comcast) was not only unfair, but ineffective in protecting your online privacy, since the “edge providers” (companies like Google, Facebook, Amazon and Netflix) are not subject to FCC regulations (but the FTC instead), and they are currently far more zealous and successful at destroying your privacy than the ISPs:

“The era of Big Data is here. The volume and extent of personal data that edge providers collect on a daily basis is staggering… Nothing in these rules will stop edge providers from harvesting and monetizing your data, whether it’s the websites you visit or the YouTube videos you watch or the emails you send or the search terms you enter on any of your devices.”

True as this is, it would be naive to expect now-chairman Pai to replace the repealed privacy regulations with something consistent with his concluding sentiment in that dissent:

“After all, as everyone acknowledges, consumers have a uniform expectation of privacy. They shouldn’t have to be network engineers to understand who is collecting their data. And they shouldn’t need law degrees to determine whether their information is protected.”

So it’s not as though your online privacy was formerly protected and now it’s not. It just means the ISPs can now compete with Google and Facebook to sell details of your activity on the internet. There are still regulations in place to aggregate and anonymize the data, but experiments have shown anonymization to be surprisingly difficult.

If you don’t like playing the patsy, it’s possible to fight a rearguard action by using cookie-blockers, VPNs and encryption, but such measures look ever more Canute-like. Maybe those who tell us to abandon the illusion that there is such a thing as privacy are right.

So, after privacy, what’s the next thing you could lose?

Goodbye Open Internet?

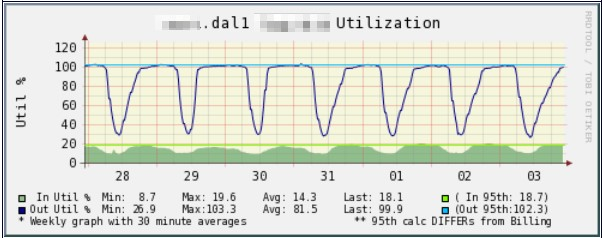

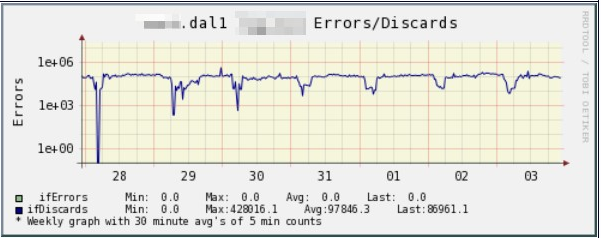

Last week’s legislation was a baby-step towards what the big ISPs would like, which is to ‘own’ all the data that they pipe to you, charging content providers differentially for bandwidth, and filtering and modifying content (for example by inserting or substituting ads in web pages and emails). They are currently forbidden to do this by the FCC’s 2015 net neutrality regulations.

So the Net Neutrality controversy is back on the front burner. Net neutrality is a free-market issue, but not in the way that those opposed to it believe; the romantic notion of a past golden age of internet without government intrusion is hogwash. The consumer internet would never have happened without the common carrier regulations that allowed consumers to attach modems to their phone lines. AT&T fought tooth and nail against those regulations, wanting instead to control the data services themselves, along the lines of the British Prestel service. If AT&T had won that battle with the regulators, the internet would have remained an academic backwater. Not only was the internet founded under government sponsorship, but it owes its current vibrant and innovative character to strongly enforced government regulation:

“Without Part 68, users of the public switched network would not have been able to connect their computers and modems to the network, and it is likely that the Internet would have been unable to develop.”

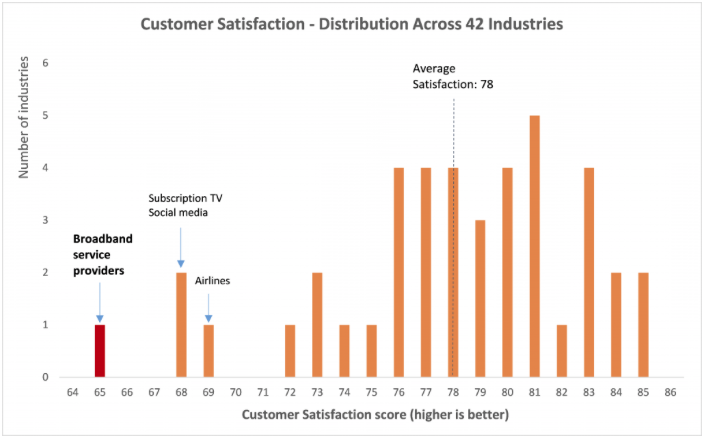

For almost all US consumers internet access service choice is limited to a duopoly (telco and cableco). On the other hand internet content services participate in an open market teeming with competition (albeit with near-monopolies in their domains for Google and Facebook). This is thanks to the net neutrality regulations that bind the ISPs:

- No Blocking: broadband providers may not block access to legal content, applications, services, or non-harmful devices.

- No Throttling: broadband providers may not impair or degrade lawful Internet traffic on the basis of content, applications, services, or non-harmful devices.

- No Paid Prioritization: broadband providers may not favor some lawful Internet traffic over other lawful traffic in exchange for consideration of any kind — in other words, no “fast lanes.” This rule also bans ISPs from prioritizing content and services of their affiliates.

If unregulated, ISPs will be compelled by structural incentives to do all these things and more, as explained by the FCC:

“Broadband providers function as gatekeepers for both their end user customers who access the Internet, and for edge providers attempting to reach the broadband provider’s end-user subscribers. Broadband providers (including mobile broadband providers) have the economic incentives and technical ability to engage in practices that pose a threat to Internet openness by harming other network providers, edge providers, and end users.”

It’s not a simple issue. ISPs must have robust revenues so they can afford to upgrade their networks; but freedom to prioritize, throttle and block isn’t the right solution. Without regulation, internet innovation suffers. Instead of an open market for internet startups, gatekeepers like AT&T and Comcast pick winners and losers.

Net neutrality simply means an open market for internet content. Let’s keep it that way!