Instat came out yesterday with a report entitled “Portable Connectivity Driving Wi-Fi Chipset Market.”

The report says:

Although dual-mode cellular/Wi-Fi handsets represented only 3% of total shipments in 2006, this category will be the breakout market segment in 2007, and will reach 20% of the total Wi-Fi chipset market in 2009.

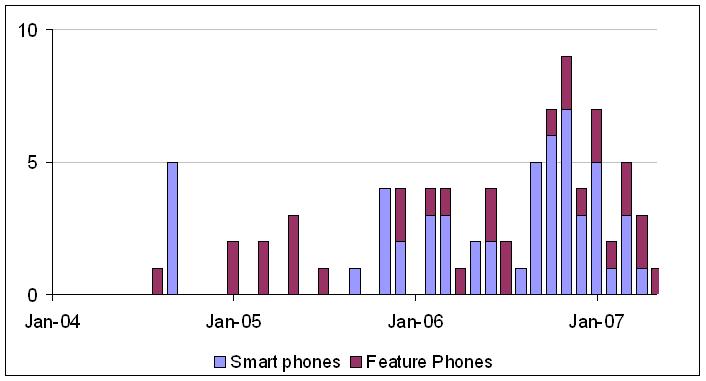

A look at the database of smartphones and PDAs at pdadb.net reveals that of 343 phones listed, 192 have Wi-Fi; of the 96 phones released since December 2006, 76 have Wi-Fi. This confirms Instat’s opinion at the top end of the phone market.

Although the smartphone market is small relative to the overall cell phone market (4% in US, 9% in Europe according to Telephia), it is still big. With well over a billion cell phones being sold in 2007, the number of smartphones will be of the order of 100 million. In another report, Instat predicts about 400 million Wi-Fi chipsets to be sold in 2009. So the 20% number seems quite doable with smart phones alone.

If FMC takes off, Wi-Fi will also become common in non-smartphones, and the volume of Wi-Fi chip sales will be even higher. But mobile network operators remain tentative about FMC; rapid widespread rollout is not happening yet. Consumers rightly see little value in FMC the way that it is currently being sold to them. FMC is more likely to be led by enterprises deploying smart phones using third party applications to extend their PBX. The mobile and fixed operators have the power to thwart this use of their networks, and some will. But the benefits of this model to enterprises are clear and compelling, so it will eventually prevail.