Please download and use the RootMetrics app.

Their coverage maps are highly informative, and the more people that contribute, the more useful the results become.

Voice on the Internet

Please download and use the RootMetrics app.

Their coverage maps are highly informative, and the more people that contribute, the more useful the results become.

I discussed last September how AT&T was considering opening up the 3G data channel to third party voice applications like Skype. According to Rethink Wireless, Steve Jobs mentioned in passing at this week’s iPad extravaganza that it is now a done deal.

Rethink mentions iCall and Skype as beneficiaries. Another notable one is Fring. Google Voice is not yet in this category, since it uses the cellular voice channel rather than the data channel, so it is not strictly speaking VoIP; the same applies to Skype for the iPhone.

According to Boaz Zilberman, Chief Architect at Fring, the Fring iPhone client needed no changes to implement VoIP on the 3G data channel. It was simply a matter of reprogramming the Fring servers to not block it. Apple also required a change to Fring’s customer license agreements, requiring the customer to use this feature only if permitted by his service provider. AT&T now allows it, but non-US carriers may have different policies.

Boaz also mentioned some interesting points about VoIP on the 3G data channel compared with EDGE/GPRS and Wi-Fi. He said that Fring only uses the codecs built in to handsets to avoid the battery drain of software codecs. He said that his preferred codec is AMR-NB; he feels the bandwidth constraints and packet loss inherent in wireless communications negate the audio quality benefits of wideband codecs. 3G data calls often sound better than Wi-Fi calls – the increased latency (100 ms additional round-trip according to Boaz) is balanced by reduced packet loss. 20% of Fring’s calls run on GPRS/EDGE, where the latency is even greater than on 3G; total round trip latency on a GPRS VoIP call is 400-500ms according to Boaz.

As for handsets, Boaz says that Symbian phones are best suited for VoIP, the Nokia N97 being the current champion. Windows Mobile has poor audio path support in its APIs. The iPhone’s greatest advantage is its user interface, it’s disadvantages are lack of background execution and lack of camera APIs. Android is fragmented: each Android device requires different programming to implement VoIP.

The always good Rethink Wireless has an article AT&T sounds deathknell for unlimited mobile data.

It points out that with “3% of smartphone users now consuming 40% of network capacity,” the carrier has to draw a line. Presumably because if 30% of AT&T’s subscribers were to buy iPhones, they would consume 400% of the network’s capacity.

Wireless networks are badly bandwidth constrained. AT&T’s woes with the iPhone launch were caused by lack of backhaul (wired capacity to the cell towers), but the real problem is on the wireless link from the cell tower to the phone.

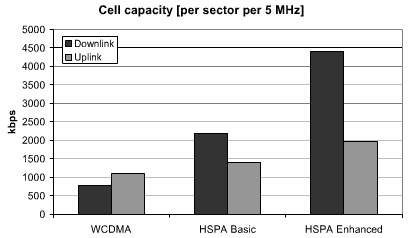

The problem here is one of setting expectations. Here’s an excerpt from AT&T’s promotional materials: “Customers with capable LaptopConnect products or phones, like the iPhone 3G S, can experience the 7.2 [megabit per second] speeds in coverage areas.” A reasonable person reading this might think that it is an invitation to do something like video streaming. Actually, a single user of this bandwidth would consume the entire capacity of a cell-tower sector:

Source: High Speed Radio Access for Mobile Communications, edited by Harri Holma and Antti Toskala.

This provokes a dilemma – not just for AT&T but for all wireless service providers. Ideally you want the network to be super responsive, for example when you are loading a web page. This requires a lot of bandwidth for short bursts. So imposing a bandwidth cap, throttling download speeds to some arbitrary maximum, would give users a worse experience. But users who use a lot of bandwidth continuously – streaming live TV for example – make things bad for everybody.

The cellular companies think of users like this as bad guys, taking more than their share. But actually they are innocently taking the carriers up on the promises in their ads. This is why the Rethink piece says “many observers think AT&T – and its rivals – will have to return to usage-based pricing, or a tiered tariff plan.”

Actually, AT&T already appears to have such a policy – reserving the right to charge more if you use more than 5GB per month. This is a lot, unless you are using your phone to stream video. For example, it’s over 10,000 average web pages or 10,000 minutes of VoIP. You can avoid running over this cap by limiting your streaming videos and your videophone calls to when you are in Wi-Fi coverage. You can still watch videos when you are out and about by downloading them in advance, iPod style.

This doesn’t seem particularly burdensome to me.

In an earlier post, I discussed a comment AT&T made contemplating allowing VoIP on the cellular data channel. Today AT&T wrote a letter to the FCC saying that they have decided to go ahead with it.

This will make international calls much cheaper for people who are willing to put up with the latency issues of the data channel.

It’s like buying an airplane ticket then getting charged extra to get on the plane.

The cellular companies want you to buy cellular service then pay extra to get signal coverage. Gizmodo has a coolly reasoned analysis.

AT&T Wireless is doing the standard telco thing here, conflating pricing for different services. It is sweetening the monthly charge option for femtocells by offering unlimited calling. A more honest pricing scheme would be to provide femtocells free to anybody who has coverage problem, and to offer the femtocell/unlimited calling option as a separate product. Come to think of it, this is probably how AT&T really plans for it to work: if a customer calls to cancel service because of poor coverage, I expect AT&T will offer a free femtocell as a retention incentive.

It is ironic that this issue is coming up at the same time as the wireless carriers are up in arms about the FCC’s new network neutrality initiative. Now that smartphones all have Wi-Fi, if the handsets were truly open we could use our home Wi-Fi signal to get data and voice services from alternative providers when we were at home. No need for femtocells. (T-Mobile@Home is a closed-network version of this.)

Presumably something like this is on the roadmap for Google Voice, which is one of the scenarios that causes the MNOs to fight network neutrality tooth and nail.

In a recent letter to the FCC, AT&T said that it had no objection to VoIP applications on the iPhone that communicate over the Wi-Fi connection. It furthermore said:

Consistent with this approach, we plan to take a fresh look at possibly authorizing VoIP capabilities on the iPhone for use on AT&T’s 3G network.

So why would anybody want to do VoIP on the cellular data channel, when there is a cellular voice channel already? Wouldn’t voice on the data channel cost more? And since the voice channel is optimized for voice and the data channel isn’t, wouldn’t voice on the data channel sound even worse than cellular voice already does?

Let’s look at the “why bother?” question first. There are actually at least four reasons you might want to do voice on the cellular data channel:

Moving on to the issue of cost, an iPhone unlimited data plan is $30 per month. “Unlimited” is AT&T’s euphemism for “limited to 5GB per month,” but translated to voice that’s a lot of minutes: even with IP packet overhead the bit-rate of compressed HD voice is going to be around 50K bits per second, which works out to about 13,000 minutes in 5GB. So using it for voice is unlikely to increase your bill. On the other hand, many voice plans are already effectively unlimited, what with rollover minutes, friend and family minutes, night and weekend minutes and whatnot, and you can’t get a phone without a voice plan. So for normal (non-international) use voice on the data channel is not going to reduce your bill, but it is unlikely to increase it, either.

Finally we come to the issue of whether voice sounds better on the voice channel or the data channel. The answer is, it depends on several factors, primarily the codec and the network QoS. With VoIP you can radically improve the sound quality of a call by using a wideband codec, but do impairments on the data channel nullify this benefit?

Technically, the answer is yes. The cellular data channel is not engineered for low latency. Variable delays are introduced by network routing decisions and by router queuing decisions. Latencies in the hundreds of milliseconds are not unusual. This will change with the advent of LTE, where the latencies will be of the order of 10 milliseconds. The available bandwidth is also highly variable, in contrast to the fixed bandwidth allocation of the voice channel. It can sometimes drop below what is needed for voice with even an aggressive variable rate codec.

In practice VoIP on the cellular data channel can sometimes sound much better than regular cellular voice. I mentioned above David Frankel’s demo at IT Expo West. I performed a similar experiment this morning with Michael Graves, with similarly good results. I was on a Polycom desk phone, Michael used Eyebeam on a laptop, and the codec was G.722. The latency on this call was appreciable – I estimated it at around 1 second round trip. There was also some packet loss – not bad for me, but it caused a sub-par experience for Michael. Earlier this week at Jeff Pulver’s HD Connect conference in New York, researchers from Qualcomm demoed a handset running on the Verizon network using EVRC-WB, transcoding to G.722 on Polycom and Gigaset phones in their lab in San Diego. The sound quality was excellent, but the latency was very high – I estimated it at around two seconds round trip.

The ITU addresses latency (delay) in Recommendation G.114. Delay is a problem because normal conversation depends on turn taking. Most people insert pauses of up to about 400 ms as they talk. If nobody else speaks during a pause, they continue. This means that if the one-way delay on a phone conversation is greater than 200 ms, the talker doesn’t hear an interruption within the 400 ms break, and starts talking again, causing frustrating collisions.

The ITU E-Model for call quality identifies a threshold at about 170 ms one-way at which latency becomes a problem. The E-Model also tells us that increasing latency amplifies other impairments – notably echo, which can be severe at low latencies without being a problem, but at high latencies even relatively quiet echo can severely disrupt a talker.

Some people may be able to handle long latencies better than others. Michael observed that he can get used to high latency echo after a few minutes of conversation.

I wrote earlier about AT&T’s responses to FCC’s questions concerning the iPhone App Store and Google Voice.

Now Apple has posted its responses to the same questions, which are basically the same as AT&T’s. Among the differences are that Apple’s responses contain some hard numbers on its controversial App Store approval process:

These numbers don’t really add up. So what Apple probably means is that 95% of the applications that have been approved were approved within 14 days of their final submission. Even so, each reviewer must look at an average of 425 submissions per week (8,500*2/40), which is 10 per hour per reviewer – an average of 12 minutes of reviewer time per submission, which doesn’t seem to justify the terms “comprehensive” and “rigorous” used in Apple’s description of the process:

Apple developed a comprehensive review process that looks at every iPhone application that is submitted to Apple. Applications and marketing text are submitted through a web interface. Submitted applications undergo a rigorous review process that tests for vulnerabilities such as software bugs, instability on the iPhone platform, and the use of unauthorized protocols. Applications are also reviewed to try to prevent privacy issues, safeguard children from exposure to inappropriate content, and avoid applications that degrade the core experience of the iPhone. There are more than 40 full-time trained reviewers, and at least two different reviewers study each application so that the review process is applied uniformly. Apple also established an App Store executive review board that determines procedures and sets policy for the review process, as well as reviews applications that are escalated to the board because they raise new or complex issues. The review board meets weekly and is comprised of senior management with responsibilities for the App Store. 95% of applications are approved within 14 days of being submitted.

Of course much of this might be automated, which would explain both the superhuman productivity of the reviewers and the alleged mindlessness of the decision-making.

The phone OEMs are customer-driven, and I mean that in a bad way. They view service providers rather than consumers as their customers, and therefore have historically tended to be relatively uninterested in ease of use or performance, concentrating on packing in long checklists of features, many of which went unused by baffled consumers. Nokia seemed to have factions that were more user-oriented, but it took the chutzpah of Steve Jobs to really change the game.

A recent FCC inquiry has provoked a fascinating letter from AT&T on the background of the iPhone and AT&T’s relationship with Apple, including Voice over IP on the iPhone. On the topic of VoIP, the letter says that AT&T bound Apple to not create a VoIP capability for the iPhone, but Apple did not commit to prevent third parties from doing so. AT&T says that it never had any objection to iPhone VoIP applications that run over Wi-Fi, and that it is currently reconsidering its opposition to VoIP applications that run over the 3G data connection. Since the argument that AT&T presents in the letter in favor of restrictions on VoIP is weak, such a reconsideration seems in order.

The argument goes as follows: the explosion of the mobile Internet led by the iPhone was catalyzed by cheap iPhones. iPhones are cheap because of massive subsidies. The subsidies are paid for by the voice services. Therefore, AT&T is justified in protecting its voice service revenues because the subsidies they allow had such a great result: the flourishing of the mobile Internet. The reason this argument is weak is that voice service revenues are not the only way to recoup subsidies. AT&T has discovered that it can charge for the mobile Internet directly, and recoup its subsidies that way. It will not sell a subsidized iPhone without an unlimited data plan, and it increased the price of that mandatory plan by 50% last year. Even with this price increase iPhone sales continued to burgeon. In other words, AT&T may be able to recoup lost voice revenues by charging more for its data services.

This is exactly what the “dumb pipes” crowd has been advocating for over a decade now: connectivity providers should charge a realistic price for connectivity, and not try to subsidize it with unrealistic charges for other services.

Well, that last post on the likely deficiencies of VoIP on iPhones may turn out to have been overly pessimistic. It looks as though Hell is beginning to freeze over. Skype is now running on iPhones over the Wi-Fi connection, and for a new release it’s running relatively well. AT&T deserves props for letting it happen – unlike T-Mobile, which isn’t letting it happen and therefore deserves whatever the opposite of props is.

6 hours after it was released Skype became the highest-volume download on Apple’s AppStore. In keeping with Skype’s reputation for ease of use, it downloads and installs with no problems, though as one expects with first revisions it has some bugs.

My brief experience with it has included several crashes – twice when I hung up a call and once when a calendar alarm went off in the middle of a call. Another interesting quirk is that when I called a friend on a PC Skype client from my iPhone, I heard him answer twice, about 3 seconds apart. Presumably a revision will be out soon to fix these problems.

Other quirky behaviour is a by-product of the iPhone architecture rather than bugs, and will have to be fixed with changes to the way the iPhone works. The biggest issue of this kind is that it is relatively hard to receive calls, since the Skype application has to be running in the foreground to receive a call. This is because the iPhone architecture preserves battery life by not allowing programs to run in the background.

Similar system design characteristics mean that when a cellular call comes in a Skype call in progress is instantly bumped off rather than offering the usual call waiting options. I couldn’t get my Bluetooth headset to work with Skype, so either it can’t be done, or the method to do it doesn’t reach Skype’s exemplary ease of use standards.

Now for the good news. It’s free. It’s free to call from anywhere in the world to anywhere in the world. And the sound quality is very good for a cell phone, even though the codec is only G.729. I expect future revisions to add SILK wideband audio support to deliver sound quality better than anything ever heard on a cell phone before. The chat works beautifully, and it is synchronized with the chat window on your PC, so everything typed by either party appears on both your iPhone and PC screen, with less than a second of lag.

After a half-hour Skype to Skype conversation on the iPhone I looked at my AT&T bill. No voice minutes and no data minutes had been charged, so there appear to be no gotchas in that department. A friend used an iPod Touch to make Skype Wi-Fi calls from an airport hot-spot in Germany – he reports the call quality was fine.

The New York Times review is here

Don’t get too excited by Apple’s announcement of a Voice over IP service on the iPhone 3.0. It strains credulity that AT&T would open up the iPhone to work on third party VoIP networks, so presumably the iPhone’s VoIP service will be locked down to AT&T.

AT&T has a large network of Wi-Fi hotspots where iPhone users can get free Wi-Fi service. The iPhone VoIP announcement indicates that AT&T may be rolling out voice over Wi-Fi service for the iPhone. It will probably be SIP, rather than UMA, the technology that T-Mobile uses for this type of service. It is likely to be based on some flavor of IMS, especially since AT&T has recently been rumored to be spinning up its IMS efforts for its U-verse service, which happens to include VoIP. AT&T is talking about a June launch.

An advantage of the SIP flavor of Voice over Wi-Fi is that unlike UMA it can theoretically negotiate any codec, allowing HD Voice conversations between subscribers when they are both on Wi-Fi; wouldn’t that be great? The reference to the “Voice over IP service” in the announcement is too cryptic to determine what’s involved. It may not even include seamless roaming of a call between the cellular and Wi-Fi networks (VCC).

AT&T has several Wi-Fi smartphones in addition to the iPhone. They are mostly based on Windows Mobile, so they can probably be enabled for this service with a software download. The same goes for Blackberries. Actually, RIM may be ahead of the game, since it already has FMC products in the field with T-Mobile, albeit on UMA rather than SIP, while Windows Mobile phones are generally ill-suited to VoIP.