The fall 2009 crop of ultimate smartphones looks more penultimate to me, with its lack of 11n. But a handset with 802.11n has come in under the wire for 2009. Not officially, but actually. Slashgear reports a hack that kicks the Wi-Fi chip in the HTC HD2 phone into 11n mode. And the first ultimate smartphone of 2010, the HTC Google Nexus One is also rumored to support 802.11n.

These are the drops before the deluge. Questions to chip suppliers have elicited mild surprise that there are still no Wi-Fi Alliance certifications for handsets with 802.11n. All the flagship chips from all the handset Wi-Fi chipmakers are 802.11n. Broadcom is already shipping volumes of its BCM4329 11n combo chip to Apple for the iTouch (and I would guess the new Apple tablet), though the 3GS still sports the older BCM4325.

Some fear that 802.11n is a relative power hog, and will flatten your battery. For example, a GSMArena report on the HD2 hack says:

There are several good reasons why Wi-Fi 802.11n hasn’t made its way into mobile phones hardware just yet. Increased power consumption is just not worth it if the speed will be limited by other factors such as under-powered CPU or slow-memory…

But is it true that 802.11n increases power consumption at a system level? In some cases it may be: the Slashgear report linked above says: “some users have reported significant increases in battery consumption when the higher-speed wireless is switched on.”

This reality appears to contradict the opinion of one of the most knowledgeable engineers in the Wi-Fi industry, Bill McFarland, CTO at Atheros, who says:

The important metric here is the energy-per-bit transferred, which is the average power consumption divided by the average data rate. This energy can be measured in nanojoules (nJ) per bit transferred, and is the metric to determine how long a battery will last while doing tasks such as VoIP, video transmissions, or file transfers.

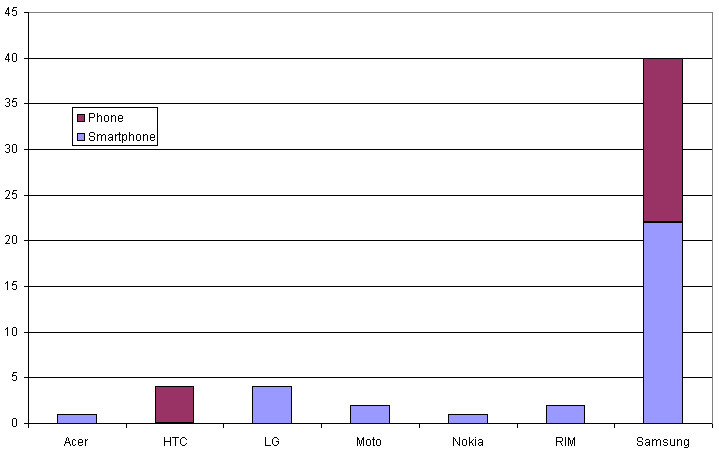

For example, Table 1 shows that for 802.11g the data rate is 22 Mbps and the corresponding receive power-consumption average is around 140 mW. While actively receiving, the energy consumed in receiving each bit is about 6.4 nJ. On the transmit side, the energy is about 20.4 nJ per bit.

Looking at these same cases for 802.11n, the data rate has gone up by almost a factor of 10, while power consumption has gone up by only a factor of 5, or in the transmit case, not even a factor of 3.

Thus, the energy efficiency in terms of nJ per bit is greater for 802.11n.

Here is his table that illustrates that point:

Source: Wireless Net DesignLine 06/03/2008

The discrepancy between this theoretical superiority of 802.11n’s power efficiency, and the complaints from the field may be explained several ways. For example, the power efficiency may actually be better and the reports wrong. Or there may be some error in the particular implementation of 802.11n in the HD2 – a problem that led HTC to disable it for the initial shipments.

Either way, 2010 will be the year for 802.11n in handsets. I expect all dual-mode handset announcements in the latter part of the year to have 802.11n.

As to why it took so long, I don’t think it did, really. The chips only started shipping this year, and there is a manufacturing lag between chip and phone. I suppose a phone could have started shipping around the same time as the latest iTouch, which was September. But 3 months is not an egregious lag.